Today, I’m excited to announce the open-source release of SheetBot, a flexible automation and CI tool I’ve been developing for nearly two years. SheetBot offers a unique approach to task orchestration using JSON Schema for dynamic job assignment, supports arbitrary scripts in any language, and requires minimal dependencies - just Deno. It’s designed for developers who want a lightweight, extensible system without the overhead of traditional CI platforms. You can find the code on GitHub at https://github.com/jorisvddonk/sheetbot.

I’ve been working on various open-source tools and games for a little over 20 years now as a hobby. Virtually all of these projects never had a developer community behind them, and I’ve eschewed any kind of revenue-generating initiatives for all of these because I prefer making money with my day job, so that I can continue making what I want to make in that which I classify as my personal time. I can be pretty lazy and forgetful on how things worked as I switch between projects, so I like automating things. For a long time, the lack of quality open-source tooling that’s free and that appeals to my sensibilities has bothered me, so early 2024 as I needed some automation for some pretty weird use-cases, I figured I’d take a stab at building something according to my preferences. SheetBot is the result of that.

Before I continue, I have to mention one thing real quick: SheetBot is provided as-is under an MIT license. It doesn’t scale, and I provide zero support. I never want to make money off of it, either. I don’t really think anyone other than myself should use it. I do however think there’s some interesting ideas in there, so for the rest of this post, I’d like to talk about why I made it, and what I think makes it nicer than other things. Please steal ideas from it you think are worthwhile.

Why I built SheetBot

I mainly built SheetBot because I needed something to help me develop System Reset, which - for parts of its testing workflows - required automating things in MS-DOS. This meant running DOS executables to validate game data consistency across different implementations (original DOS game vs. modern remakes). This was the primary factor, but I’ve thought about building something like this for at least 10 years prior, since in my opinion, other free/open-source CI systems suffer from a bunch of things.

First off, they simply have too many dependencies (PostgreSQL, MySQL, MongoDB, Redis, JVM)1. I operate on a self-imposed budget of zero Swedish Krona per year, and I’m just a solo developer working on something in a “I don’t care if I lose some build (meta)data” mindset. Sure, a nice separate database with a backup plan is nice for a production environment at scale, but I don’t operate that way. I care about self-hosting, and it should be as easy as possible with ideally no maintenance, because I do want to pretend that I have a life outside of this hobby.

Many CI systems have expectations and opinions on what build/configuration scripts should look like. These opinions are either strong and I don’t like them 2, or they’re weak which causes a combinatory explosion of hundreds of valid configurations, which makes finding the right information applicable to my use-case needlessly difficult. As you continue reading you’ll notice that SheetBot also has strong opinions on configuration, but this time I like them so it’s totally fine! And actually it doesn’t have opinions on build scripts at all, which is such a key thi— err.. I should not spoil too much. Just read on.

Have I mentioned that many CI systems don’t make cross-platform development easy, if they even care about it? The status quo seems to be “you have the ability to run a shell script or powershell script, and you can use that to run something that makes everything cross-platform”.. Yay!? Sure, that ‘solves’ the cross-platform need, but now the CI system is a glorified shell script runner. Surely we can do better? Actually, yeah, some do better - by doing everything in a language like Python for which there’s an intepreter for virtually every system you can imagine, but they get overly opinionated again, optimize for super narrow use-cases, or suffer from suboptimal software ecosystems inherited from the tech of their choice…

I run some old, slow or archaic hardware/software environments, like a Raspberry Pi Zero W, MS-DOS/FreeDOS on an old laptop, a bunch of 4G USB sticks that were convinced to run Debian 11, some VPSes I somehow still pay for, cool gaming handhelds running Linux (Steam Deck and various Anbernic devices), and various 32-bit mini PCs running whatever flavour of Linux/BSD I wanted to play around with at the time. I’d really like to build stuff on these things as well, and maybe test things on them too, but running a Java-based agent on these just doesn’t work well in practice3.

Pictured: two 4G USB sticks running Debian 11 literally on top of another Debian 11 machine

Pictured: two 4G USB sticks running Debian 11 literally on top of another Debian 11 machine

I treat these systems as “pets, not cattle”4. Personal machines I boot up only when needed for builds or tests, rather than always-on infrastructure. This approach works well with my self-imposed zero-budget lifestyle and avoids maintenance hassles, but it clashes with CI systems expecting constant agent connections.

I’m a programmer and I like to extend things so that they fit my bespoke use-cases. Many CI systems don’t make this trivial, or they require a language-specific build system. I’m getting older and I’m using too many of these across hobbies and my day-job, which has meant that usually, instead of spending time making my life easier by extending such a CI system, I just shrug and ‘make do’ with something I know can be improved.

Similarly, many CI systems have their configuration in a database. This kind of sucks when you’re a solo dev and you don’t want to set up backup procedures for databases, as it means that you can lose days’ worth of config when your database borks out because you didn’t perform the necessary monthly rituals with candles and incense to calm the machine spirits. I don’t need that, and neither do I need some weird bespoke versioning system inside of a database that allows me to rollback to a previous config. I’ve got git already, and I’m using private repositories in GitHub, so why can’t I store my config in my code instead!?

Another pain point: some of these CI systems require that you set up the server first, and then the runners, because runners have to be provisioned with software that can only be downloaded from the server and isn’t available elsewhere5. Wild. Whilst this doesn’t really matter much for my use-cases, I have been very annoyed with this professionally6, so I’ve been keen to avoid this.

Okay, I should wrap it up, so here’s a few more annoyances with existing CI systems:

- They don’t make it trivial to get (meta)data out of the platform for quick bespoke analysis. Need to integrate with an API or run a SQL query!? Bleh! Let me copy-paste things via UI easily, please!

- They have very weak forms of job orchestration, so builds often fail because of out-of-memory, out-of-diskspace, or dependencies not being available.

- They don’t expect to be integrated with or called from another program, like a game engine. It has to be their runner, which has to then invoke that other program. Not a big deal honestly, but I’ve often found myself thinking “if only this were possible, then I could make a much nicer system that works way faster!”

- They treat structured data storage as an afterthought, or something done via a plugin. Want to capture milliseconds-per-frame performance data and fail a build if you don’t meet a target? Good luck, here’s OpenTelemetry for collection, a Grafana plugin for visualization, and a shell script that also parses the underlying source data and exits with a nonzero exit code when you’re over your perf budget! Sigh.

- They have weak built-in security and permissions systems and rely on OS-level isolation or (usually) instance-level isolation or network isolation. I don’t necessarily think that’s bad, but I do appreciate some defense in depth.

(For what it’s worth, SheetBot provides some defense in depth through Deno’s security model and SheetBot’s JSON Schema-based task assignment - tasks can only run on workers that explicitly match their capability requirements, providing a form of runtime validation beyond just OS-level isolation. Tasks also run in their own isolated process and can be configured to require specific credentials or network access patterns.)

Okay, hopefully you’re now suitably convinced CI/CD systems leave something to be desired. So let me tell you about the thing I made that also leaves things to be desired - just different things.

Primitive Emergent Architecture

Okay. But first. A quick sidebar..

I’ve always been fascinated with this concept I call ‘primitive emergent architecture’; a style of software where simple primitives are designed to combine in interesting ways, leading to systems that do more than originally intended. It’s similar to the Unix Philosophy: small programs that compose into bigger things via stdin/stdout, files, and pipes. Once you understand those concepts, you can automate entire workflows easily.

This mindset influences how I build things. Instead of minimal viable products that only handle specific use-cases, I aim for elegant designs that can expand into use-cases I already know I want to support a few months down the road. It has caused friction with project managers who prefer predictable scopes, but it leads to systems I’m proud of. SheetBot is my latest example; its primitives combined to create a flexible orchestration layer that has been surprisingly versatile.

I should really talk about SheetBot

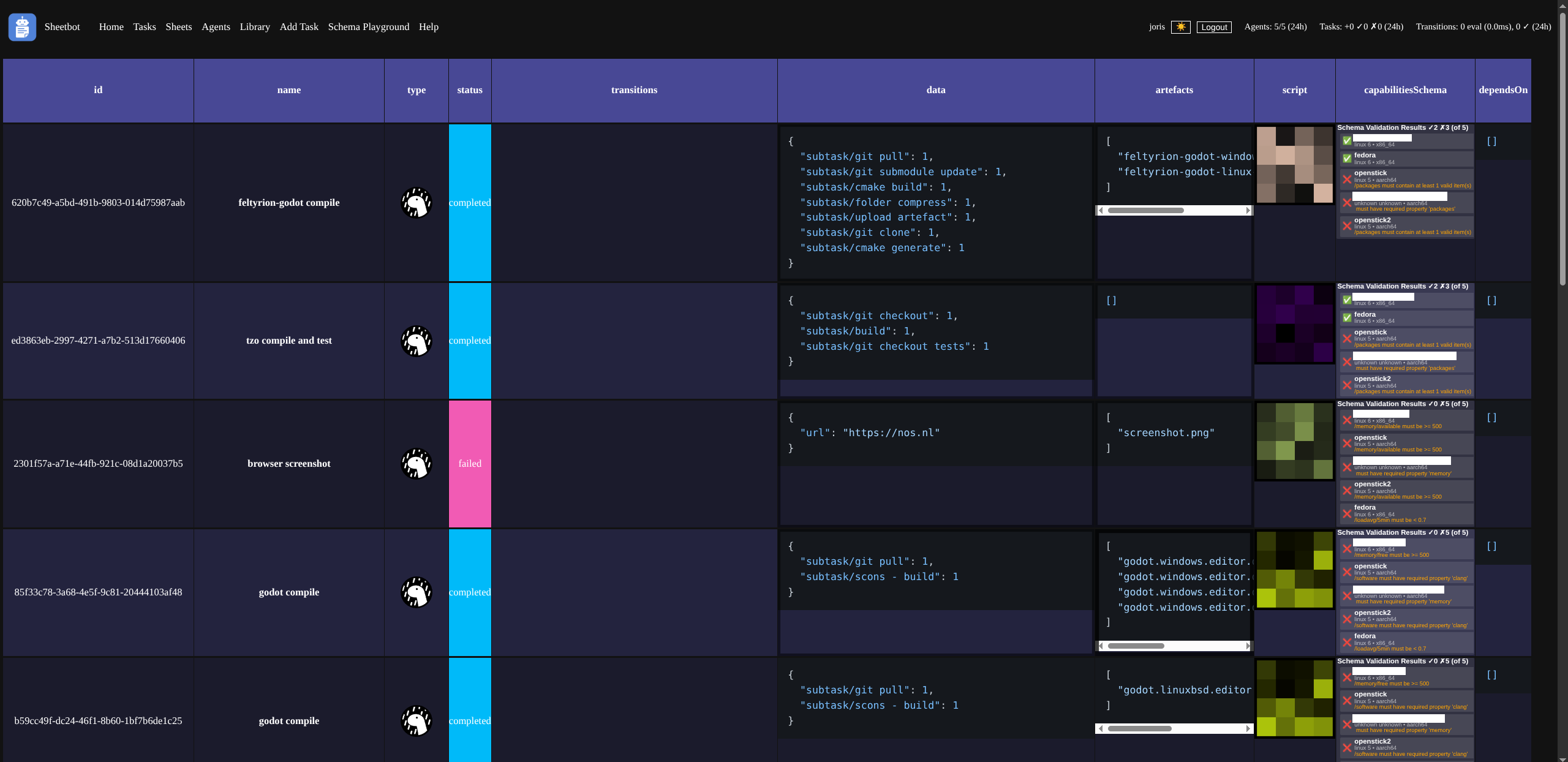

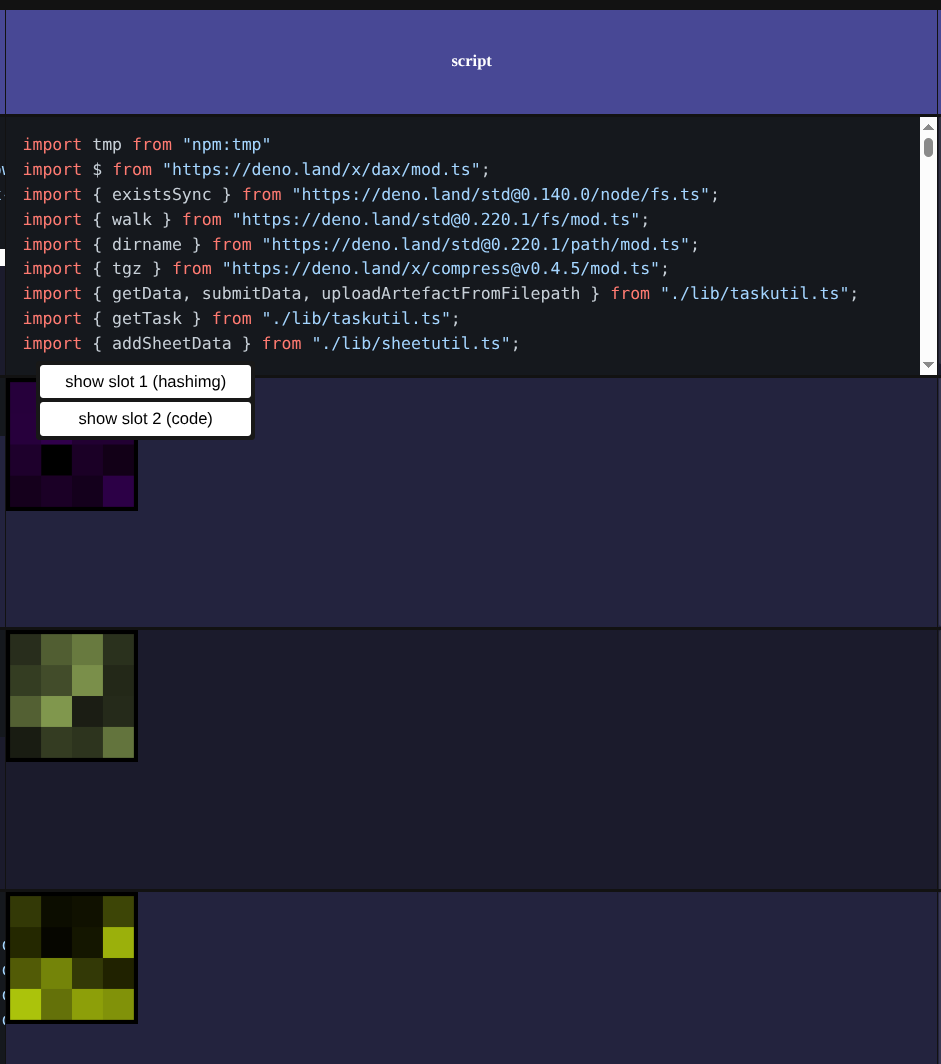

SheetBot originated from my need for a better CI system to test feltyrion-godot builds across platforms. Experimenting with Deno, I created a build_and_test.ts script hosted on this site, ran it via deno run --reload -A on multiple PCs, and monitored builds manually. The system worked well but required manual monitoring, so I quickly built a backend with Express.js for data storage and a frontend. The initial version ran builds continuously, supported only one job with client-side subscription, but showed potential.

So I went out on a hike in one of Southern Stockholm’s nice nature reserves, thinking about better ways of doing things that would help me build a better system. I wanted something simple yet powerful, with a few concepts working together in harmony in a way that encouraged combining them into much more bespoke and advanced patterns, that encouraged writing configuration and bespoke modifications straight into the code, that could dynamically pick up arbitrary opaque tasks based on arbitrary opaque system parameters and metrics, with a flexible and extensible UI system built around modern web standards, that didn’t require any build system itself, and with just one dependency - Deno.

I settled on five key technologies I’d be using for this:

- Deno - because I liked how it made things simple whilst supporting proper TypeScript, and I wanted to form stronger opinions on it.

- Express.js - because I knew it well and it’s never let me down, so I wouldn’t give it up.

- SQLite - because it’s super simple and it would allow me to put the database files under version control.

- Web Components (Lit) - because I wanted some frontend component system that didn’t rely on a build system.

- JSON Schema - because I’ve used this in the past and had a hunch it could be a fantastic way of doing task orchestration7.

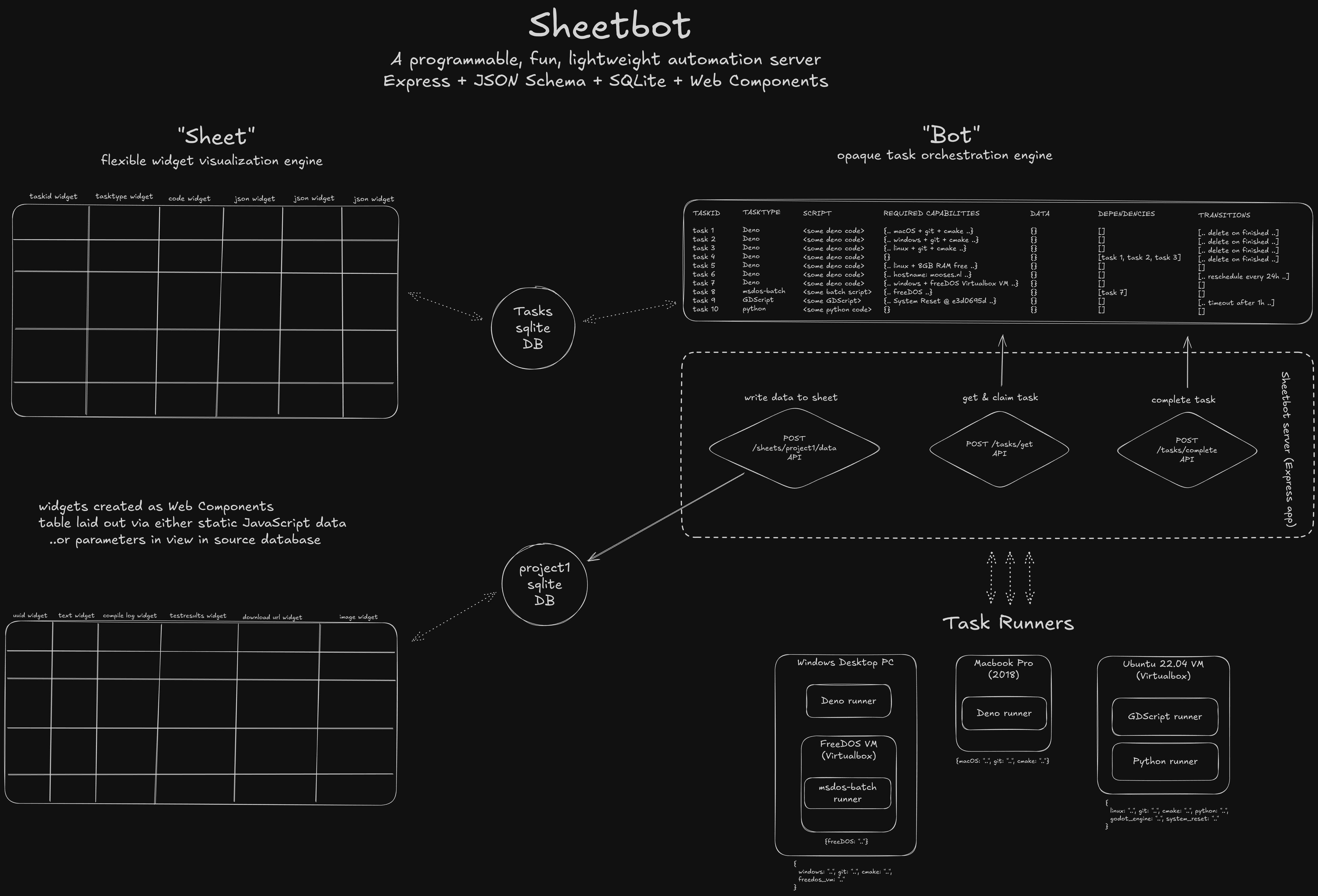

I also settled on a name (THE MOST IMPORTANT THING!!) referring to the two critical things I wanted it to be:

- A flexible widget visualization engine (“Sheet”)

- An opaque task orchestration engine (“Bot”)

The SheetBot API

The inner workings of SheetBot are relatively straightforward:

An HTTP API would allow you to add ‘tasks’ to a queue using POST /tasks. In the POST body you’d provide an arbitrary script8 and a JSON Schema. These would then be stored in a SQLite DB, together with some task status metadata.

To get a task for execution on a worker node, on the node your ‘task runner’ script (more on that later) would make a POST /tasks/get call9 with a “capabilities” JSON Object as the payload. This call would return the first available task whose JSON Schema validated against your “capabilities” payload.

For clarity, here’s an example of a JSON Schema that I use for some of my tasks10, which ensures at least 500MB memory is available and the 5 minute load average is not terrible, indicating that a system is idle enough to run some jobs:

{

"$schema": "http://json-schema.org/draft-07/schema#",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"memory": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"available": {

"type": "number",

"minimum": 500

}

},

"required": [

"available"

]

},

"loadavg": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"5min": {

"type": "number",

"exclusiveMaximum": 0.7

}

},

"required": [

"5min"

]

}

},

"required": [

"memory",

"loadavg"

]

}Here’s what a typical worker’s “capabilities” payload might look like - it reports everything the system knows about itself, from hardware specs to installed software:

{

"os": {

"os": "linux",

"release": {

"version": "6.8.0-51-generic",

"major_version": 6,

"minor_version": 8,

"patch_version": 0

}

},

"arch": "x86_64",

"packages": [

"git",

"clang",

"cmake",

"node",

"deno"

],

"hostname": "ubuntu",

"software": {

"git": {

"version": "2.43.0",

"major_version": 2,

"minor_version": 43,

"patch_version": 0

},

"clang": {

"version": "18.1.3",

"major_version": 18,

"minor_version": 1,

"patch_version": 3

}

},

"memory": {

"total": 961.6171875,

"free": 88.4921875,

"available": 250.43359375,

"unit": "MB"

},

"loadavg": {

"1min": 0.3,

"5min": 0.2,

"15min": 0.1

}

}The worker node would then POST /tasks/:id/accept to accept and ‘claim’ the task, run it, and call POST /tasks/:id/complete or POST /tasks/:id/failed with data depending on the outcome of the task.

Arbitrary blob data for tasks could be written and read via S3-compatible(ish) API11 at any stage of a task.

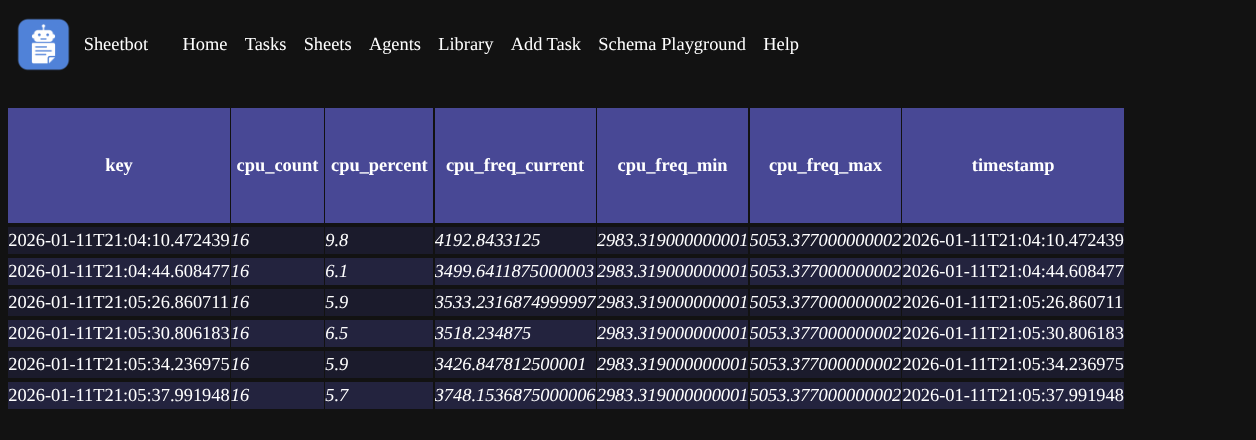

Any additional structured data that transcended individual task boundaries could be submitted by a call to POST /sheets/:id/data with a key and fields object as body; these would then get stored to a separate SQLite DB, their columns expanded as new fields were added. This creates dynamic schema evolution - if you submit data with a new field, SQLite’s ALTER TABLE adds that column automatically. Type changes aren’t supported (you’d need to recreate the sheet), but this makes it easy to collect data over time without upfront schema design.

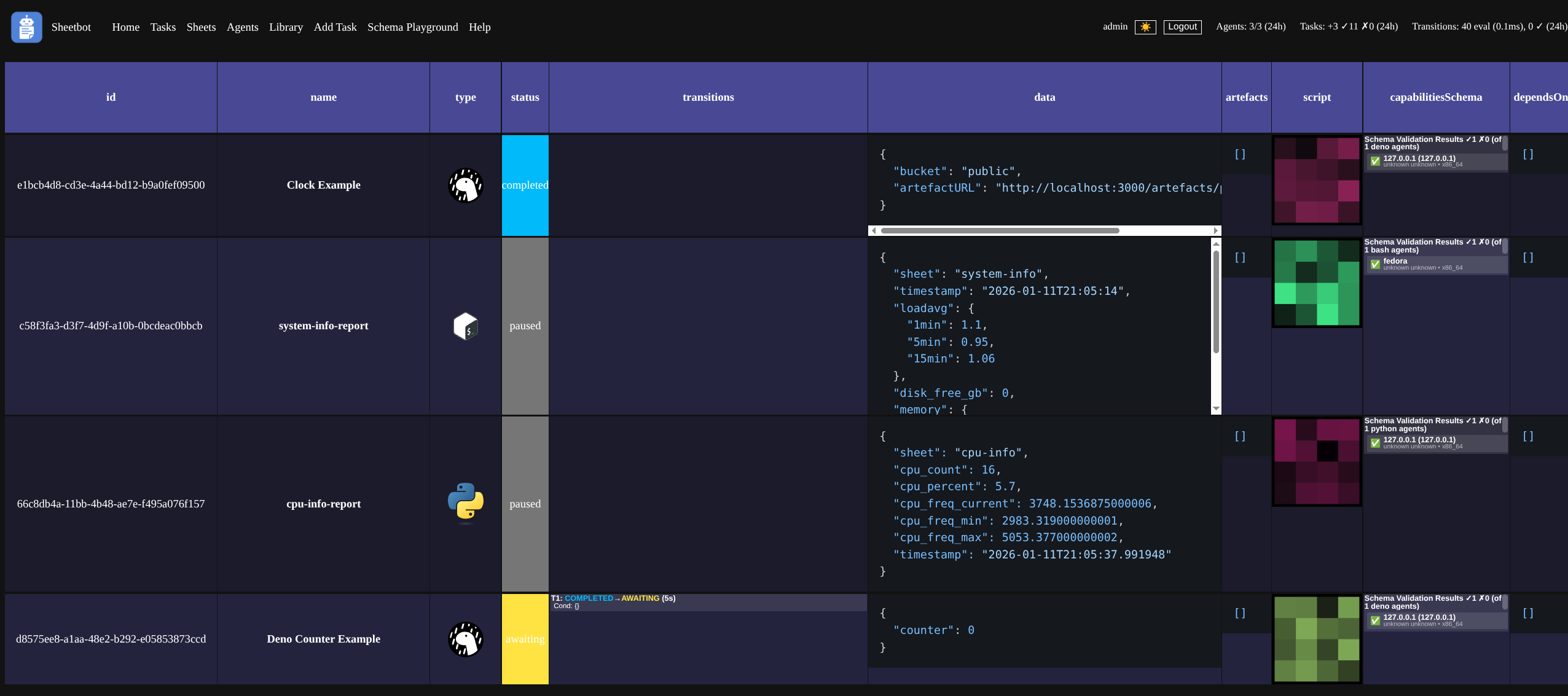

A web frontend would fetch tasks and sheets, and render them as an HTML table with cells for columns wrapped inside configurable Web Components (more on the UI later).

…These ideas took me two weeks to validate and build alongside development of my other projects. I have made some additions since: tasks can now depend on other tasks, and tasks can transition between states automatically or periodically based on JSON Schema12. But those initial core concepts still exist in SheetBot today, and they’ve served me well for almost two years, for more use-cases than I could imagine back then.

Conceptually, this looks like this (you probably want to right-click and open in new tab):

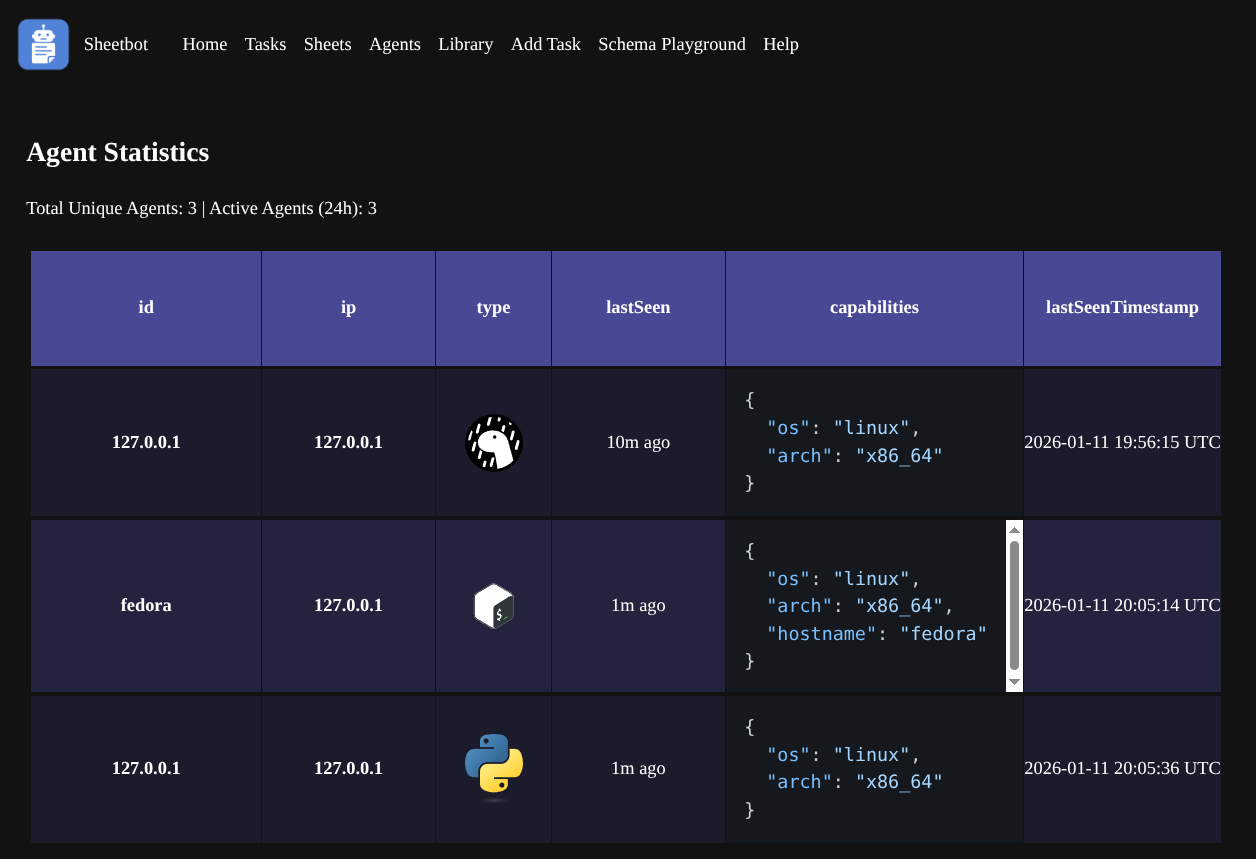

A quick note on ‘task runners’ (agents)

I kind of mentioned earlier that I didn’t like agents and I don’t like how some CI systems require you to download an ‘agent’ or ‘runner’ from the CI system itself. I still don’t like that. And SheetBot technically kind of doesn’t have ‘runners’. Except it does. Sort of.

The truth is, when you’re designing any kind of system like this, you’re really defining a “contract” that can only be fulfilled by software that knows what that contract is and implements it, even if the contract itself is as trivial as I’ve written it above. So; an agent.

My first ‘agent’ was a Deno agent. It was so simple you could write it out on a napkin and implement it in less than an hour. Later on I implemented Python and Bash agents as well.

For all of these agents I ended up creating a dynamic endpoint that returns the exact runner script with a bunch of useful URLs baked into the script itself, so all you need to do is something like:

deno run --reload https://<sheetbot base url>/scripts/agent.tsto run a Deno ‘agent’uv run --script https://<sheetbot base url>/scripts/agent.pyto run a Python ‘agent’curl -fsSL https://<sheetbot base url>/scripts/agent.sh | bashto run a Bash ‘agent’

… with the correct credential environment variables set, of course.

Now, this way of working is totally optional. In fact, you could totally just download these scripts from GitHub here and provide them with the correct environment variable or modify them slightly to ensure the correct SheetBot base URL is used. This makes it possible to do all of this via provisioning scripts without requiring the server to be active first, which simplifies things quite a bit!

Agents use a sophisticated capabilities system to report what they can do to the server. Each agent maintains three layers of capabilities:

- Static capabilities (

.capabilities.json) - manually defined configurations - Dynamic capabilities - automatically detected software versions, memory, OS details, etc.

- Override capabilities (

.capabilities.override.json) - final modifications

This allows precise task matching - for example, ensuring compilation tasks only run on agents with the right cmake and compiler versions and sufficient memory.

A key distinction from traditional CI systems is that these “agents” are not persistent daemon processes that maintain a constant connection to the server. Instead, they run as cronjobs or on-demand scripts that periodically execute, retrieve an available task that matches the worker’s capabilities, run it, and then exit. This aligns perfectly with treating systems as “pets, not cattle” - workers are ephemeral and only active when needed, making it trivial to spin up new workers on any system without complex agent registration or persistent connections.

So does it work well? What are the use-cases?

It turns out that this core idea - tasks containing arbitrary scripts that run on worker nodes depending on conditions validated through JSON Schema - works really well. Exceptionally well. I’ve been really happy with it;

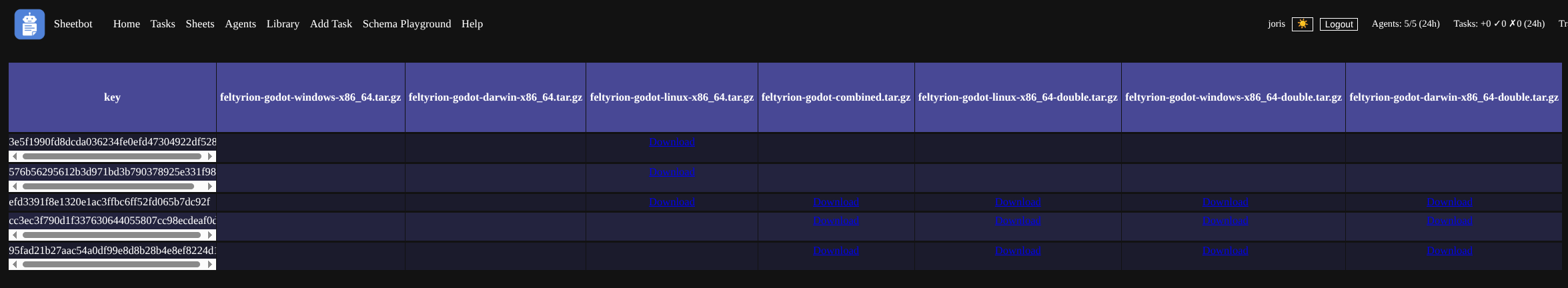

I’ve written cross-platform build scripts in TypeScript and Python that emit build artefacts and build results back to SheetBot. One of these is for a custom Godot editor build for System Reset, and I make those available through SheetBot for anyone that wants to work on the game.

I’ve automatically installed cmake on all my nodes remotely by creating a bash task script containing sudo apt-get update; sudo apt-get install cmake13 that was governed by a JSON Schema that would activate it on Debian-based systems that did not have cmake installed yet and that had at least 1GB of free disk space available on the system disk. This task had a transition schema that would return the task back to ‘awaiting’ state after completion so any other system without cmake installed on it could pick it up later for another run. The nice thing about this is that you don’t need to write checks in the bash script that checks for Ubuntu or Fedora or Debian or Arch Linux; JSON Schema takes care of ensuring it only runs on systems with apt and passwordless sudo.

Transitions work by defining conditions under which a task should change states. For this cmake task, the transition looked something like: “If the task is COMPLETED, reset it to AWAITING after 5 minutes” - this way, the task becomes available again for systems that might not have had cmake installed when it first ran.

I’ve written a task that would turn off my Hue lights between 02:00 and 07:00 local time. The JSON Schema would ensure it only runs on worker nodes within my Tailscale network that have access to a home assistant daemon running at home.

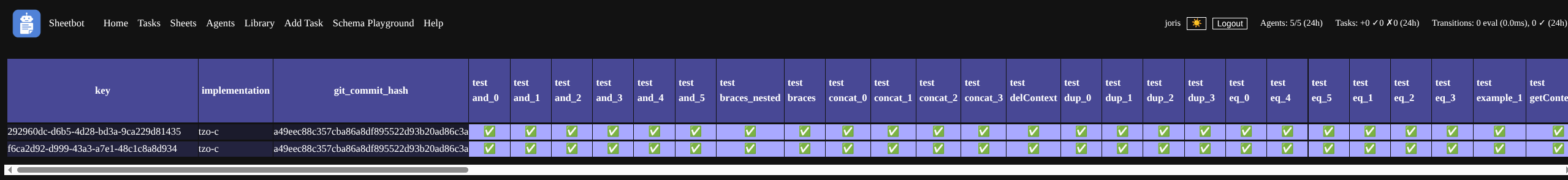

I’ve written test scripts that would validate my Tzo language implementations against a test suite and report on their status in a nice table, so I could compare and contrast the various implementations.

I’ve written MS-DOS task scripts that would download a Noctis IV save state, run the game with a parameter to take a dump of a planet texture, upload the results, and write the URL to the uploaded dump in a sheet. I’ve done the same for System Reset as an editor-loadable GDScript plugin. I then wrote another script that would retrieve the sheet, look for missing data in the ‘validation’ column, and for all missing data it would compare the dumps for consistency across implementations and write out semicolon-separated numbers into that column containing the index offsets of all inconsistencies. A custom widget for that column would then render the textures and highlight the differences visually.

(Sadly I don’t have this available to show anymore as I changed the way uploading of blobs works and I haven’t updated the scripts since. I should get around to fixing that…)

There’s a lot that can be written and automated with this! This website is published through a SheetBot task that never gets deleted. When I want to publish a new version, I simply move the task manually from COMPLETED to AWAITING.

The UI

The UI is… Suitably spartan?

I’ll admit I don’t think it’s very pretty. But it’s functional and has some neat features.

- All data visualisation is done through HTML5 ‘sheet’ UIs! You can navigate with arrow keys, click and drag to select multiple cells, hit ctrl-c and then paste either as text, or even as a table in a spreadsheet program!

- Sheets are backed by data, and render widgets that show that data in some way. When you copy, you copy the backing data - not the widget. The copied data is stored in the clipboard as both plaintext with tabs and newlines, and as a rich table, so that you can paste it in Excel for bespoke analysis.

- Columns can have multiple widgets. When a column has multiple widgets, right-clicking on a cell shows a context menu that allows you to switch between them. The ‘script’ column defaults to a hashimage view, but you can show the actual script content (text) too!

I often use sheets for things like download links:

..or system info:

I know it’s honestly not pretty, but it’s very flexible and it works suprisingly well.

The AI section of this post

Okay, you might’ve seen this one coming. If you want to skip my evaluations on how well SheetBot works with AI, you can skip ahead to the next section.

So. In late November 2024 I started using AI assistance tools in Visual Studio Code. I wasn’t super impressed at first but these tools helped with a function here or there to do some boring typing for me. Then, in March 2025, Claude Code and Amazon Q Developer CLI were released, and suddenly I found that AI-assisted coding was actually quite viable.

A lot of the code of SheetBot since that moment has been written using tools like those and OpenCode. I understand that might put some people off, and that’s honestly okay. But personally, I’ve found that SheetBot’s architecture works exceptionally well with AI. Widget development is a breeze; you simply point the AI tool to an existing widget, and tell it to create one like it but with a different use-case instead. Need integration with some kind of identity provider? You could prompt it and I’m sure your assistant will throw in some kind of middleware for Express that does it for you. Sticking with well-known and well-documented libraries and technologies really turned out to be a great decision, as it allows me to leverage AI assistance without having to blow up their context size with my own bespoke technologies.

This has made me really excited about both the concept of configuration as code, and extensibility through code without plugins. Specifically using scripting languages that don’t have a compile step, and promoting leverage of AI tooling to configure and extend. I think it really lowers the barrier to configuring and extending projects like these for more sophisticated and bespoke use-cases, without burdening maintainers.

I have more to write on the subject, but I’ll leave it there. If you want to take a fork of the project without any AI influence, the state of the project at this commit is what you want for now.

Advanced Features

One of SheetBot’s more experimental features is the Distributed Promise Runtime, which allows writing natural async TypeScript code for orchestrating distributed tasks using the Deno agent runner:

// Define distributed functions

// Distributed functions get turned to tasks automatically by the runtime

const compile = distributed(

async (src: string) => runCompileJob(src),

{ properties: { os: { const: "linux" } } } // capabilities JSON Schema

);

const zip = distributed(async (...files) => zipFiles(files));

const upload = distributed(async (file) => uploadFile(file));

// Write natural async code

(async () => {

const [libfoo, libbar] = await Promise.all([

compile("libfoo.cpp"),

compile("libbar.cpp")

]);

const result = await upload(await zip(libfoo, libbar));

console.log("Final result:", result);

})();The runtime automatically infers and executes a DAG of tasks across agents, making distributed computing feel like local async code. This uses SheetBot’s existing task system but provides a much more intuitive programming model for complex workflows.

This is super experimental and I want to explore it more. I haven’t seriously used it in my existing (private) use cases of SheetBot yet, but I do want to start using this for System Reset’s build and release flows.

What’s next?

I don’t know. Well, now that I have open-sourced SheetBot, I need to find a way to decommission my own private fork of it so I have a single repo I work with instead of two. Once that’s done, I’ll continue working on it to add features I need.

I’m probably going to add a few more agent runners. I’ve played around a lot with αcτµαlly pδrταblε εxεcµταblεs and cosmopolitan libc recently and might try creating a simple, cross-platform, cross-architecture, single-binary runner that can perform basic tasks and shell out to other cosmos programs. It might also be interesting to port SheetBot to redbean.

I don’t want to be on the hook to support others that are using it because I don’t really like the codebase all that much myself and I suspect there’s some interesting race conditions. I haven’t hit them, but my usage of SheetBot itself is fairly limited; I mainly use it to automate things like baking a release of System Reset. But if someone wants to fork it, steal ideas from it, or take it into its own direction, they’re totally fine to do so within the terms of the license!

Hope you enjoyed this post, and can take some inspiration from SheetBot. If you want to give it a try yourself, feel free to grab it here, but please only use it for your homelab!

P.S.: thanks to all of the folks of the various CI systems that I used in the past that I’ve been able to interact with in various ways. Despite some of the criticism I’ve written above, I do actually really quite like systems like Jenkins, BuildBot, Concourse, and even closed-source ones like TeamCity, Unreal Horde, etc. Special thanks to the Jenkins developers that I met at FOSDEM a few years ago; I forgot your names but you were pretty awesome and gave some really good feedback on my ideas!

Footnotes

-

This is where I thank Docker and

docker-compose, which have really made this much easier than it was 20 years ago! Nevertheless, not something I want to run and operate, and especially not develop on. ↩ -

Groovy? Always a pain as I don’t write it a lot. YAML? Please no. Shell scripts? Meh, too slow and sequential. ↩

-

I don’t want to spend hours trying to get Java running there without breaking other runners through lack of forwards/backwards compatibility with a Java-based CI system. Okay, this is probably solvable on anything that has more than 256MB RAM, so maybe ignore this criticism. I’m just not super skilled with this, and neither do I want to be. ↩

-

I do enjoy the irony of this, given that professionally I focus really hard on treating systems as much like cattle as possible at significantly larger scale. I suppose I do this because it allows me to stay in touch with other ways of doing things that many people still live and work by. ↩

-

Actually I don’t think any system actually does this this egregiously, but they do make it really difficult to obtain the right agent runner because there’s no public artefacts or you need to perform some login to some system to be allowed to download. ↩

-

Ugh, writing Terraform for these kinds of situations - or creating agent images - is terrible as you have to chain into some kind of provisioning system or do things lazily on agent boot which slows things down. Not ideal for ephemeral autoscaling instances. ↩

-

By “task orchestration” I mean the ability to dynamically assign tasks to workers based on worker capabilities. Instead of manually configuring which worker runs which job, JSON Schema allows workers to describe their capabilities (memory, CPU, installed software, etc.) so that SheetBot can provide them only matching tasks. ↩

-

‘Arbitrary’ meaning: SheetBot doesn’t care what format it’s in and it doesn’t inspect the script either. It could be JavaScript. Could be a shell script. Could be a binary blob. Could be a Magnet URL, Ansible YAML, Hashicorp Configuration Language, human-written prompt. Could be a picture of a honey badger. Sheetbot don’t care. ↩

-

Ah, yes, the

POSTto/tasks/get. Yeah, it makes me puke, too. I wish I’d just done aGETwith a body, or aQUERY, but some implementations of some HTTP libraries don’t support either of these, so I had to cave. Sigh. ↩ -

Worth noting here that these JSON Schemas are also completely abstract. There’s no formal definition here that needs to be adhered to, but in the public release there is some opinionated defaults that I’ve been using that I think work well, which allow matching not just on free disk space, but also CPU architecture, installed software, and even installed software packages, because - for example - Deno 2.x is quite different from Deno 1.x. ↩

-

Virtual ‘S3’ ‘buckets’ are automatically created for tasks. I did at first explore a simple S3-like API, and later on explore WebDAV, but both kind of sucked as they weren’t easily mountable as a filesystem using FUSE, and various clients failed to mount these WebDAV volumes, so I switched over to S3-compatible API as it is a little more widely used. I did consider adding NFS support, as that would make things really nicely mountable on Linux systems, but that would likely require an external third party tool, or a very slow implementation in JavaScript. ↩

-

Transitions automatically change task states based on conditions defined in JSON Schema. For example, a completed task can be reset to “awaiting” state after a delay to run periodically, or a failed task can be marked for retry. This enables complex lifecycle management without custom code - you just define the conditions under which a task should change states. ↩

-

Yeah, this would actually temporarily require passwordless

sudo. Not ideal and I’ve played around with an idea to allowsudopasswordless on my systems only based on approval through a push notification. Not sure if such a system exists. If it does, let me know because I’d love to use it! ↩